3-Waying Eels for BIG Stripers!

By Stu Adams

Although a favorite striper bait is live or fresh bunker, eels are a staple for many anglers. And for good reason. They catch big fish! Eels are readily available throughout most of the season and prove to be quite hardy. They can be kept alive practically forever in a cool, dark place.

Stu with a monster bass caught on a live eel.

Keeping Eels

I prefer to store eels in a dark blue or black bucket in the basement. I learned the hard way that if you keep eels in a white bucket, they bleach out, turning almost white themselves. On trips where we had both fresh, dark eels, and leftover albino-looking ones, the darker eels out-fished the lighter ones. I had to witness this on several occasions before I could actually believe it wasn't just a fluke, but it proved true again and again. Now I'm a believer, and thus, a dark bucket.

In addition to a bucket, you’ll need an air pump. I use a $5 aquarium pump. Depending on whether there are six eels, or a couple dozen in the bucket, determines how often I change the water. If you walk downstairs and it stinks, you haven't gone down there often enough! The key is to check it every few days. If it's clouding up, change it. Regular cold tap water is fine. The chlorine doesn't seem to have any effect on these hardy souls.

The author keeps a supply of 10”-12” eels at home, so that he’s always ready for fishing.

To make transporting the eels easy, I keep them in a black drawstring mesh laundry bag. I hang the string of the bag on a peg on the wall. The bag just barely touches the bottom of the bucket. The mouth of the bag is far enough into the air that even the most determined eels can't crawl up to the opening. It was after multiple attempts at trying to create a lid that would let air in, but not let the eels out, which led to the discovery of this simple, yet effective solution. I’m no longer sniffing out dead eels from under the washing machine.

Storing & Handling

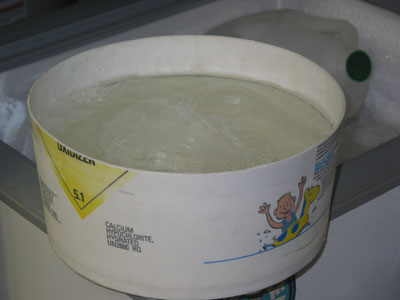

The best method for storing eels on the boat is to put them on ice. Ice keeps the eels fresh and slows them down, making them easier to hook. Instead of submerging the eels in ice water—where they can drown while dormant—I prefer to put them on a block of ice. To make the ice block, I put 3-4 inches of water in the cut off bottom of another 5 gallon bucket and place it in the freezer.

When I’m ready to go fishing, I place the ice block in a bucket that’s the same diameter as a typical 5-gallon bucket, but stands 2/3 as tall. I use a chlorine bucket I purchased at swimming pool store. It has a screw-on lid that prevents it from being blown off while trailering or running across the Sound. Next, I place the inner bucket with the ice block on top of a 5-gallon bucket. I drilled a bunch of holes in the bottom, so as the ice melts it drains into the bigger bucket below.

I then put the cut off bottom of yet another 5 gallon bucket with holes drilled as pictured, on top of the ice to keep them from direct contact with the ice. Finally, I put the bag of eels on top of that. Keeping the eels in the bag makes them easier to grab, rather than chasing them around on a block of ice. The block will last an entire trip, as opposed to cubes or crushed ice. This system has worked with great success for me in keeping eels alive.

Hooking

Even when slowed down by ice, eels can be a little hard to handle. First, I lay the hook on the deck next to the bucket within easy reach. Then, I use two hands to grab the eel with a rag. A piece of an old mesh laundry bag makes an effective tool for holding on to these slippery little devils, even when wet.

Use two hands to grab the eel. Then, manipulate the eel until you get a firm grasp with one hand, with just the head sticking out of the rag. Hold the eel over the bucket and run the hook through. The first time you lose a hold of one and it gets loose on the deck, you’ll remember to keep it over the bucket.

Thoughts on where to place the hook vary. Some anglers go from side to side behind the head. I feel I get better movement out of the eel by going bottom to top through the mouth, being careful not to go too far back into the head and kill it. As soon as I hook the eel, I throw it over the side into the water, where it can swim. Laying it on the deck, or dangling the eel in the air, can lead to the eel tying itself into a nasty “eel knot”, which you’ll inevitably discover is nearly impossible to undo.

When you encounter that nasty tangle, the easiest solution is often to remove the hook from the eel while it is still in the knot. It will usually relaxed itself and drop free from the tangle. You can then rinse the slime off the line and more easily untangle the knots(s) in your line. You may now have to go from side to side when re-hooking the eels to avoid using the same hole, which could allow it to slip off the hook too easily.

Tackle

I prefer a rod that isn’t too soft in the tip, yet is far from being a broomstick. My favorite rod is a Seeker “Black Steel” model # G670-7’ rated for 20 to 50-lb. line. The 7-foot Seeker handles 8-12-oz. weights nicely. Although I like the Seeker, you’ll need to choose the rod that’s right for you.

I match the rod with a conventional reel spooled with 50-pound super braid line. In fishing eels, I like braided line’s sensitivity, strength and ability to cut through the water, getting you to the bottom quickly.

Swivels & Weights

At the end of the braided line, I used tie to a swivel using the quick and effective Palomar knot. Now, I use what for me has proven to be stronger -- the twice through the eye, improved clinch knot. I still use the Palomar for all the knots tied with mono.

In the past, I used a three-way swivel, but the line would get wrapped around the swivel on the drop, so I've switched to a regular swivel. I tie both the main line and the sinker dropper line/loop to the same end, and then tie the leader to the hook on the remaining end. The main line pulling against the sinker on the same ring tends to keep the swivel straight out to the side towards the hook. I tie a leader and sinker to the other ring of the swivel. I still get it twisted, but to a much lesser degree than with a 3-way swivel.

Instead of the typical 3-way swivel, the author prefers a black standard swivel and 8 to 12-oz. bank style sinkers when fishing with eels.

Leader

Schools of thought differ on leader test. One idea is to use a lesser pound test on your leader than your main line. This is so the leader breaks first when hung up, preventing the loss of the entire rig. Another idea is to use 80# mono to the hook. The thought here being that the heavier line is much thicker, and therefore stays straighter. I use a 40# mono for my leaders. You decide what's right for you.

Regarding leader length, when I first started fishing eels, I was using 4 to 5 feet to the hook and about 2 feet to the sinker. Two feet to the sinker turned out to be a big mistake, with the two leaders getting twisted together on almost every drop. Shortening the line to the weight to about 6 inches made all the difference in the world. However, I still like a long 4 to 5-foot leader to the hook.

Hooks

Circle hooks are an all around excellent innovation in fishing. They land more fish and are safer for the fish. After setting standard hooks for over 40 years, learning to fish circle hooks took a few trips. With circle hooks, you simply reel in when you get a bite. You don’t set the hook. Circle hooks are ideal for any novice fisherman you may take out, who hasn’t learned to set the hook.

A circle hook does less harm to fish and has a better hook-up ratio than conventional hooks.

In 1999, I caught 101 stripers on my boat with circle hooks. Only three of these fish weren’t hooked in the corner or top of the jaw. This ratio proved to me that circle hooks work as described, making them excellent for catch and release.

The Drift

The drift is the most important part of fishing eels. Sometimes I hear of anglers not having success with eels. When I ask where they fish, they generally name some very productive areas, which tells me that their technique, and not the location is what needs to be changed.

I look for the rockiest spots I can find. The more irregular the bottom, the better. Big bass are lazy. They like to tuck themselves in behind the boulders to avoid fighting the current. It doesn't take much to provide the break they need. A small boulder is all it takes.

Boulder strewn reefs also provide plenty of food. Even on any given reef, some spots are rockier than others. If you can detect the boulder fields, or even small clumps, that's where you want to be. Some of my most productive spots are no bigger than the size of your garage. As soon as I feel soft bottom with the sinker instead of rocks, it’s time to make the drift again, unless of course I'm certain another stretch of boulders lay just ahead.

Stu with a nice bass that couldn’t resist a live eel.

A close-up of the scale reveals the weight: 39.13 lbs!

When I first arrive at a spot, I stop directly over it, put the boat in neutral, and drift while I attach the sinker and rig an eel. This helps me determine the direction of my drift, including the wind factor.

Once I position for the drift, I wait until the boat has stopped its forward motion, and has begun to start drifting back with the tide, before I drop down. This helps to prevent letting out more line than necessary. As soon as the sinker hits bottom, I come up three turns with the reel handle. I occasionally experiment with two to four turns, but generally it’s three.

You want to keep your eel a fairly constant distance off the bottom. Since the bottom contour varies dramatically, even over very short distances, constant adjustment is required. I continually watch the depth finder so I know whether it’s getting deeper or shallower.

If the bottom is coming up, you don't want to drag the bottom for two reasons. The first and most obvious is that you can get hung up and lose a rig. Secondly, I believe that clanging a sinker along the bottom spooks the stripers.

Depending on the bottom, as well as the speed of the current, I sometimes find it necessary to adjust the depth of the bait as often as every ten to fifteen seconds. Seldom do I drift more than twenty to thirty feet without having resounded the bottom. Going fifty feet before doing so is unusual. Continually sounding the bottom with your sinker is to me the single most important aspect of fishing eels. No other single factor affects your success to such a degree.

Finally, there’s one more great reason to sound the bottom often. Although a striper in a somewhat lackadaisical state may pass up the opportunity to jump on an eel swimming by, instinct practically forces him to grab an eel that is heading towards the bottom, knowing that once it gets there, the meal will almost certainly be lost. A striper practically has no choice in the matter. Some of the most vicious hits I’ve ever experienced have come on the drop.

Closing Thoughts

The techniques described here are neither the best, nor the only methods of three-waying eels for stripers. If you've never tried three-waying at all, you've gotten a fair introduction and a good place to start. You’ll soon find yourself adjusting and modifying certain aspects of these techniques to fit your own preferences. Good luck and good fishing to all!

© ctfisherman.com and Stu Adams 2003. All Rights Reserved.